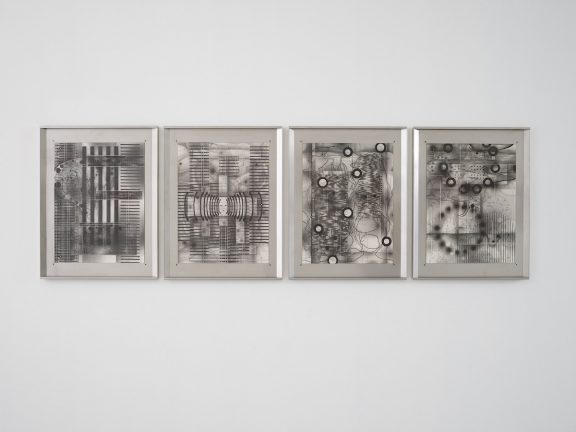

Guillaume Dénervaud

Surv’Eye

Exhibition from March 19 till April 23, 2021

Opening March 18, 2021 (Nuit des Bains)

Constellations

By Dean Kissick

During the Nineties, when Elise was at school in the English countryside, there was a constant flow of UFO sightings and crop circles, in which complicated but harmonious patterns of spiralling orbs would appear cut into wheat fields overnight, and reports of ethereal abductions on lonely country roads. These abductions were usually in the United States, and again happened overnight. Aliens would come down and snatch American men and sodomize them, for their experiments. The Nineties were fantastic, she thought. Now that old sense of excitement about and openness to the cosmos was gone. There were no more lights in the sky, no more encounters of any kind. No more geometry appeared on the farms. Steel monoliths sometimes arrived on Romanian hillsides and deserts. But no one thought about space anymore. What was space good for now?

“To separate us from God,” her friend Sam would tell her, would write to her. Sam was one of her only friends left. It was hard to hold onto friends, as she grew older and more focused, and hard to make new ones too.

She disagreed but would ask, – What does God look like? Can you draw them for me?

She had enjoyed school. Not all of it, but for the most part she’d enjoyed school, and decided at a young age she was going to be a scientist. So those years at school were a good time for her. Elise enjoyed mathematics and physics and the steeplechase. Her math teacher had decorated the walls of their classroom with colourful pictures of space: photographs of faraway galaxies and constellations, places they would never go, where it was unlikely any person would ever go, her teacher said, and phenomena no-one yet understood, which it was unlikely anyone would ever understand, but which they might someday see. They hadn’t seen anything of the universe, he said. The teacher was afraid of some of his students and some days his hands would shake in front of the whiteboard. His classroom was cheap and rundown and he’d purchased and put up those pictures himself in the hopes of brightening it. Now, when she tried to remember his classroom, Elise couldn’t recall anything but his whiteboard and his colourful pictures, which she would sit at her laminate desk looking over at, dreaming of other worlds.

There’s a small café on the shopping street in the town where she lived with her mother, still, where Elise went every morning or afternoon for a treat, and to be around other people, though rarely to converse with them. In the café she’d think of places she wanted to visit and watch the other customers going about their days. Nobody seemed to have much to do. When she noticed someone that looked a little different, somehow interesting, like this person who seemed unusually impatient, she’d watch them in brief, intermittent passages and wonder – Who is this person? If they were reading a book, she’d try to see what it was, without them noticing, and if it was one she approved of or that piqued her curiosity she’d imagine discussing it with them. If she thought she would probably like this person, she’d generally imagine they might like her too, this impatient person reading a book about cigarettes. Everyone was in their own worlds. She often wondered what everyone was thinking of.

It was once thought that gods lived on top of certain mountains, like Shiva on Mount Kailash, Aphrodite on Olympus. Like Wakea, Papa Hanau Moku, Poli’ahu, Lilinoe, Wai’au, Kahoupokane, Lea, La’amaomao and Kukahau’ula on the shifting, sacred volcanic heights of Mauna Kea, in Hawaii, which had once been theirs but was now home to thirteen large telescope observatories, some of which Elise had visited, when she’d had her research job. The sky for her was a window to the stars. Those sacred mountains, where the gods had once lived, where the radio observatories watched, over which there were ongoing conflicts between Native Hawaiian protectors and astronomers planning their Thirty Meter Telescope, were thin places, and Elise hoped to visit as many such places as possible. Thin places are places where our world grows closer to others. Places where the distance between our world and the heavens collapses, and we’re able to catch glimpses of divinity, or the romantic sublime. Often they were hidden away in an old building in an old city, or a cave which couldn’t easily be accessed, or a tunnel or distant field, but the sorts that astronomers liked, where they could site their very large telescopes, were high up on mountains surrounded by oceans, as far from the cities, the suburbs and the spills of light pouring into the sky as could be. The cosmos would fold over and reveal itself to them. It was from these thin places that they looked for, among many other phenomena, other forms of life.

When astronomers looked deep into space and time, and listened to the sounds of the universe, and analysed those sounds for patterns, and for signs and languages, for the first time, they were astounded by how perfectly silent it was, how empty of life it appeared to be. And they spoke about what they should do. So after they’d spoken, they broadcast themselves over radio waves into empty space. They posted drawings and recordings of themselves into the universe, like messages in bottles floating out across time’s waves. Artworks were sent up on rockets and lost. More radio waves, more different frequencies. But nobody ever responded. Everything was so quiet and so empty. When she imagined this emptiness, Elise thought of it as passages of colours, punctuated with objects catching the light of the stars, like a musical score with nobody to play it. What did God look like, she wondered again.

She had read an interview with a European photographer, who was always interested in the latest photographic and imaging technologies, and how they might change our understanding of the world, in which he’d said that were it possible to prove that the universe contained a number of planets similar to Earth, and so to demonstrate the mathematical probability of extra terrestrial life, religious leaders would no longer be able to hold onto their anthropocentric image of God as resembling us, as a mirror in the sky. This would become untenable, the photographer suggested, and religious leaders and their followers, and everyone else, would have to adopt a new humility; as had happened before, in Copernicus’s time, when it was shown that the sun, and not the Earth, was at the centre of the universe as they then understood it, correcting the prevailing and widespread misapprehension of the cosmos and opening the curtains to the dawn of modernity, and the present. The artist had become obsessed with this idea, he said. The interview was more than a decade old, but Elise had found the text online and printed out a copy for herself, and shared the link with Sam as well.

It was more than a decade old, and some of the events it described had since occurred. With their radio telescopes, computer models and other parts of thin places, astronomers had shown that the universe contained a great number of planets like ours, and demonstrated the likelihood of extra terrestrial life. According to latest models, there were a hundred billion planets in the Milky Way, billions of which were probably habitable worlds, and that was just in our galaxy. There were around two trillion galaxies in the observable universe. These overwhelming probabilities had been found, but nobody had changed their image of God. People were shot, stabbed, beheaded over the image of God, but through all of this, the image kept following the form of a man.

For Elise, if the models of probability suggested otherwise, the hard evidence told another story, in which she, and every other person on Earth, was absolutely alone. They had looked so far out into space and hadn’t found any signs of life of any kind. Only the great eerie silence of the cosmos. They were all alone, floating in space. Each day she liked to walk to her favourite café, which had great salads and carrot cakes, to look at the people there, imagine the lives and dreams they might have, and the conversations she might have with them. She’d left school nearly three decades ago. Were she able to sail, to accelerate over the galaxy, in 25 light years she might arrive at the young planetary system of Alpha Piscis Austrini, which looked like an exploding cosmic eye, drawn with dusty cerulean and pale amber fire, glinting with long-tailed comets.

In 39 light years, if she sailed in another direction, she would reach the faint star TRAPPIST-1, where seven Earth-like planets orbited so closely around each other she could stand on one and watch the others passing right overhead, enjoying the views of their upside-down landscapes curling by. In 63 light years, though Elise knew she wouldn’t live so long, after the exocomets, rings of dust and planetesimal belts thought to be orbiting it, she could fall, with the falling evaporating bodies, onto Beta Pictoris. And in 360 light years, in her dreams, she would arrive at Rho Ophiuchi’s star-forming clouds, which was a swinging pastel ring of four dancers made of young stars, twirling circumstellar discs, dark fragments and the songs of the spheres.

These photographs glowing from her phone, like those on the walls of her old classroom, had been taken with giant telescopes from dark mountains in Hawaii, and Chile, thin places like those. Some weren’t really photographs, but models and visualizations put together with powerful computers. One was made with eight telescopes chained together into an Event Horizon Telescope the size of Earth. They were captured in black and white and coloured in by scientists from NASA and other agencies according, in part, to their own aesthetic sensibilities, because they couldn’t know for sure how places and events so far away might look to our eyes, which will never set sight on them. These telescopes could detect colours too faint for us to see, subtle colours within colours, and wavelengths invisible to us. Space is a collection of abstractions drawn on a monumental scale. Pictures of space are expressionist paintings in a palette chosen to express the astronomer’s feelings and emotions. This would be a nice job for her, she told herself: to choose the colours for space.

If we look at the night sky, as you always should, she wrote Sam, unless it’s cloudy, we imagine those colours from pictures of space, those grape sodas, sour cherries and faint milky strawberries, we imagine those colours in space, although we can’t see them, only the darkness of night. She thought of the cosmos as a tone poem of colours, even though she couldn’t see them. She imagined colours lighting up somewhere on the other side of the darkness. This was also how we lived every day, she thought, in the darkness, imagining all the colours that aren’t there, filling in the world how we wished for it to be.

Guillaume Dénervaud’s exhibition Surv’Eye is supported by the Fondation Nestlé pour l’Art, the Fonds cantonal d’art contemporain, DCS, Geneva, Department of culture and digital transition of the City of Geneva and the Fondation d’entreprise Hermès.